Thursday, June 17, 2010

Prized Possession

It's really not even mine. It's Meredith's; she lent it to me two years ago when we shared a wall and the yard that I first read it on. She had read it for a class, said I might like it. I'd never heard of it, didn't consider the great depression among my realm of obsessions. But immediately after opening it, the book became a road map, a compass, a sacred ancient tome by a prophet not of this world, a paper limb.

I could have bought my own copy in the past two years-- whenever I'm in a bookstore I head straight for the A's, hoping there's more by him there, or that James himself will be perusing the beginning of the alphabet too, ready to share more secrets. But usually there's only another copy or two of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. A muscular volume, the the humble pale green of the spine greeting me like a friend I skinned knees with. And I always think of buying it, nine or so bucks to own it myself. So I flip it open, scan the pages. And they're bare. No underlines, starred passages or creased corners Meredith made during class (the eyes of a trapped wild animal, or of a furious angel nailed to the ground by its wings, or however else one may faintly designate the human 'soul,' that which is angry, that which is wild, that which is untamable, that which is healthful and holy, that which is competent and most marvelous and most precious...), lines that I've marked, and copied and recopied and since adopting (seizing, really) the loaner.

And the one at the bookstore was never on that yard, when we were still students, children on a blanket in the sun on a weekday afternoon. And it didn't come with me west, to California, then Portland, on to Michigan, then to Thailand, sitting in my carry-on like my only friend in the world.

(what's the use of trying to say what I felt.)

And somehow, between the months and the pages my own story has been seared into this volume. Vital scraps stuck absent-mindedly between pages: the ultimate safe-keeping place, an impeccable record is kept.

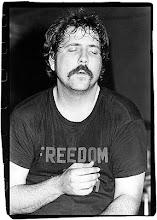

I open the front cover-- that face lined with exhaustion and dignity that has become Agee's own in my mind-- to find first a postcard from a friend visiting San Fransisco, addressed to my first house in Portland-- the address now a synonym for both infinite freedom and deadening defeat in equal measure, and nothing in between.

Next, a postcard bearing Frida's photographed portrait, purchased at the SF MOMA on my 23rd birthday, spent with Kelly-- art museum and burritos in the mission-- we owned the world.

A photograph taken my last spring in Burlington, later tried to draw its young leaves and new sun but couldn't come close to their brilliance.

A flier from a local winery in Portland.

And over the face of the first portrait in Walker Evans' series, on a sticky note: a website and number of a student loan agency, to whom I owe money, the rest of my life. I've never called the number.

Halfway through the book-- a flier for a booking/design collective in Burlington. The fall show schedule. Our social calendar in a town with just enough going on. Franzia, board games, b-movies when there wasn't.

Reciepts from a sushi dinner in Seattle-- my first week out West. $11.04-- avacado role and a Sapporo. Another receipt-- $3.50-- another Sapporo. Playing dress-up with other adults. I felt childish and mature at the same time, fearless and terrified. On the brink-- of the world, of what I would be in it. The sun set orange over the water and the warm June breeze sighed through it and I took a breath, found a home, in that.

"Small wonder how pitiably we love our home, cling in her skirts at night, rejoice in her wide star-seducing smile, when every star strikes us sick with fright: do we really exist at all?"

Tree bark I intended to press and write a letter on: the bronze paper skin of the Madrona. Its home Northern California, where Kelly and I spent a summer in the river re-organizing what we'd collected over the years in our minds re: our lives in the world. the futures that laid sprawling before us, boys. Suddenly the bark is a postcard from that time and place, far and away and long ago, now.

And finally, toward the end, between 292 and 293, a January letter from my sister, one of the hundred since we've been apart, since I left where we were for some idea of "more." Two young girls on the front of the card she made: "They remind me of us... although I'm quite thrilled that neither one of us have the boney arm belonging to the girl on the left," she says. "This weather reminds me of last winter, when we were together.... I only hope it can be that way again."

(what's the use of trying to say what I felt.)

And now, it sits on my desk in Thailand, in a school where I am somehow a teacher, not a student. Nine thousand miles from where I first picked up the book, but somehow closer than I've been in a while.

(but I am young: and I am young, and strong, and in good health; and I am young, and pretty to look at; and I am too young to worry; and so am I, for my mother is kind to me; and we run in the bright air like animals, and our bare feet like plants in the wholesome earth: the natural world is around us like a lake and a wide smile and we are growing: one by one we are becoming stronger... and one by one we shall loosen ourselves from this place, and shall be married, and it will be different from what we see, for we will be happy and love each other... it will be very different.)

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment